After I was a child, dwelling in Lawrenceville, Virginia, I heard tales about how the James River was haunted: maybe by the spirits of Indigenous individuals who have been pressured off this land, or perhaps by those that gave their lives to revolution, or perhaps by enslaved males, girls, and youngsters who drowned whereas attempting to flee their plantations. The ghost tales appeared to go well with a river that’s related to America’s soul. Supernatural or not, the James carries a sure significance, touring by the capital of the Confederacy after which to the primary colonial capitals, following the contours of the nation’s story. It’s a wellspring for historians and conjurers alike.

One of many biggest of these conjurers is now gone. D’Angelo, the musician born Michael Eugene Archer, died on Tuesday after a battle with pancreatic most cancers. He was an enigma who outlined a musical period, a recluse who battled his personal demons, a runner who—within the custom of his forefathers—sought a modicum of liberation for himself and his individuals. At simply 51 years outdated, D’Angelo joined the ranks of many Black luminaries who shined brightly however not lengthy.

For a lot of D’Angelo’s profession, critics appeared to most recognize his brilliance by means of comparability. After the discharge of his 1995 debut album, Brown Sugar, he was anointed because the vanguard of the nebulously outlined “neo-soul” sound—a modern-day Smokey Robinson with straight-back braids. Together with his follow-up masterwork, Voodoo, D’Angelo was deemed an inheritor to Prince, one other funk virtuoso whose sex-charged music upended R&B orthodoxy. What that kind of reward appeared to worth most wasn’t essentially what D’Angelo was saying or attempting to do, however the bygone mastery he evoked. For an artist who had alchemized his assortment of Prince, A Tribe Known as Quest, Roberta Flack, and Marvin Gaye information into a phenomenal sound of his personal, this was by no means a slight. However it did all the time really feel like a flattening of a sort.

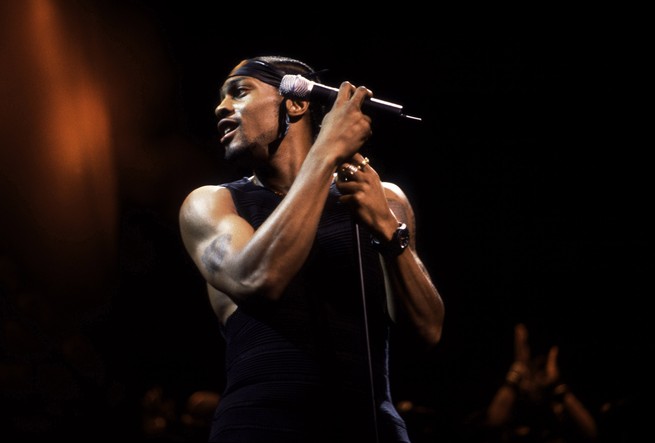

This flattening was evident in different methods too. Any variety of obituaries and tributes have talked about the music video for his hit single “Untitled (How Does It Really feel),” wherein a seemingly nude D’Angelo sang on to the digicam and, at instances, towards his unseen pelvis. The video was thought-about near-pornographic by many viewers, and it went as near viral as was attainable within the pre-social-media world, driving the business success of the only and the album. At concert events, screaming followers started to demand that D’Angelo strip, some even throwing cash on stage. Because the legend goes, the wave of objectification was so large that it despatched him into seclusion for greater than a decade.

In interviews through the years, D’Angelo tried to downplay that model of the story, however what’s clear at the least is that he felt discomfort over the concept of his picture turning into larger and extra vital than his music. He was born in Richmond, Virginia, and raised in one other city on the James River, rising up in a fire-and-brimstone Pentecostal church the place he discovered piano and different devices at an early age. Because the son of pastors, he’d absorbed the dogma that man was inherently fallen, and totally irredeemable with out the grace of God. One technique to declare that grace was by shows of spirit, which the precise music may coax out of even probably the most staid congregants. Whereas preachers preached, D’Angelo discovered ministry from the choir stand, main the flock to epiphany one measure at a time. He by no means left behind that intentionality of function, even when music grew to become enterprise.

However the church additionally taught that the ability of music could possibly be corrupting. There have lengthy been debates in church buildings about whether or not simply listening to worldly music was sinful, not to mention enjoying it. Music may carry individuals to sin simply as simply because it may carry them to salvation, and if its holy iteration introduced the devoted to the climax of talking in tongues, then its unholy model promised a climax of the flesh. D’Angelo discovered energy on this duality, smashing the obstacles between the non secular and the secular, as had so many Black music pioneers earlier than him. He constructed songs about intercourse with chords from a Hammond organ that sounded prefer it was nonetheless plugged in at a choir loft. He described the capitalist pursuit of wealth as a satan’s discount, and spoke of curses positioned on him by vengeful root-workers. In borrowing from a patchwork of references, and steeping them in a brew each sacred and profane, D’Angelo was doing greater than homage. He was conjuring.

As properly considered Voodoo is, it’s not often mentioned as a press release about Blackness and the world. Raphael Saadiq’s woozy bass line and fiery guitar licks announce “Untitled” as a transparent Prince tribute, and the album’s sonic peak. However instantly after, “Africa” straight samples Prince, and likewise channels the Purple One’s underrated penchant for commentary. In that music, D’Angelo makes use of the event of his son’s beginning to contemplate his ancestry. The drums are light and stirring; the association evokes a pulsing lullaby. Written with Angie Stone, D’Angelo’s former companion (who additionally died earlier this 12 months) and the mom of considered one of his kids, the music ponders what it means to be half of a bigger story of grief, hope, and battle. “Africa is my descent / and right here I’m removed from dwelling,” he sings. “I dwell inside a land that’s meant for a lot of males not my tone.” The lyrics place the music, and maybe the album, as one thing of an inheritance, a legacy that may reside past its creators’ lives.

D’Angelo clearly seen his personal creations otherwise than many onlookers. The try by critics to outline his work as “neo-soul”—and by extension, to generally solid his collaborators and fellow vacationers as homage acts—was all the time instructive. “I by no means claimed I do neo-soul, you realize,” D’Angelo advised an interviewer in 2014. As a substitute, he most well-liked to say that he made “Black music.” Not a recycling, however a continuation—a protracted communion with the useless, the dwelling, and the yet-to-be born.

This was all maybe most evident on D’Angelo’s third studio album, which turned out to be his swan music. Black Messiah, launched after a protracted hiatus—which included documented struggles with dependancy and psychological well being, and associated authorized troubles—was messier and fewer desirous about abiding by style than his earlier efforts. There have been stabs at attractive lounge jazz, a melodramatic Latin guitar ballad, even a folksy blues quantity. But the songs, located within the melange of Black music, cohered by D’Angelo’s resolve. The album’s musical expansiveness was matched by the breadth of its social commentary. On “Until It’s Achieved (Tutu)” he worries about local weather change, and presents a conundrum that’s newly related in at present’s flood- and fire-stricken America: “The query ain’t ‘Do now we have sources to rebuild?’ It’s ‘Do now we have the desire?’”

In “1000 Deaths,” D’Angelo’s voice is almost drowned by the chaotic combine, a wall of guitar and bass that evokes apocalyptic hearth and uprisings in Black ghettos. The lyrics are purposefully troublesome to parse, however they aren’t with out that means. In what capabilities because the music’s refrain, D’Angelo sings, “As a result of a coward dies a thousand instances / however a soldier solely dies simply as soon as.” In chanting “Yahweh, Yeshua”—the Hebrew names for God and Jesus Christ—he presents himself as a soldier for the godhead. However his Christ is Black. The album’s title calls again to this picture of a revolutionary Black Jesus, a Messiah for America’s fashionable racial strife. It additionally references the key COINTELPRO program, run by the infamous FBI director James Edgar Hoover and designed to infiltrate and sabotage civil-rights organizations throughout the nation. Within the late Sixties, Hoover’s workplace despatched a memo warning of the potential rise of an earthly Black “messiah,” a frontrunner who would possibly unite Black communities in opposition to American oppression.

D’Angelo and his collaborators had meant for Black Messiah to be launched in 2015, and lots of the songs had existed in some type for years. However in 2014, rage within the streets of Ferguson, Missouri, over the killing of Michael Brown by police helped stoke a motion that formed the subsequent decade of American life. The band and studio labored feverishly to get the report out in time to fulfill the second, and it arrived within the winter of 2014. It was not D’Angelo returning to the world, however the world lastly catching as much as him.

If the continuing American crises of tradition, know-how, and authorities share a standard thread, it’s the regular advance of—for lack of a greater time period—faux shit. Our telephones are turning into pocket-size casinos, providing windowless retreats from the actual. Bots argue with bots on social media, and the slop churned out by AI is then regurgitated by completely different AI. The inventory market appears ever extra divorced from financial fundamentals, and the American army is being ordered round by a person who watches information clips of his personal debates and rallies and grows satisfied by his personal made-up arguments. On the backside of our splintering actuality, there may be nonetheless actual artwork—actual endeavors, inspirations, and emotions. However increasingly more, they’re coated in mounds of faux shit.

To me, one antidote for these malaises is the embrace of craft for craft’s sake. D’Angelo may grow to be a patron saint for this ethos. He was infamously explicit, and his relative lack of studio output in contrast along with his friends wasn’t a results of disinterest in making music, however quite the other. He made so a lot music, each throughout the studio and with out, however he solely deemed part of that corpus price sharing with the world.

The standard containers of albums and singles by no means gave the impression to be sufficient to carry his intentions. D’Angelo approached making music the way in which Black grandmothers strategy making biscuits on Sunday earlier than church; the way in which dorm hair braiders strategy stitched cornrows; the way in which bandleaders in New Orleans strategy second strains; the way in which fire-and-brimstone preachers strategy Easter service; the way in which quilters strategy quilting. Drawing on information handed down from the ages, they work exhausting to good their craft, not simply due to the promise of a transaction or consumption, however as a result of the doing is the factor. So it’s with making music, and the inconceivable activity of assigning type to the ineffable. Typically the method is sluggish, painful, inefficient, or imperfect. However we don’t make artwork as a result of it’s fast and simple.

One widespread Black people analog to the craft of music-making is that of witchcraft. Robert Johnson bought his soul for the blues; Jimi Hendrix was himself a voodoo chile. On this custom, there’s something transcendent or ethereal in regards to the energy of music, and about these educated to wield it, who elevate the useless and stir the dwelling. However as in witchcraft, the method could be arduous and unsure. And it all the time prices one thing.

Even probably the most unbelievable tales of roots and voodoo have all the time captivated me, not essentially as a result of I need to consider, however as a result of I see in them makes an attempt to elucidate the actual ways in which human endeavor and expertise prolong past the physics of this world. In these tales, rivers are likely to have particular significance: as ritual websites, as fonts of mystic power, as locations the place you would possibly depart one world and enter one other. For many who search the opposite aspect, whether or not it’s with Charon within the Styx or the ferryman on the James, some form of craft is critical.